United Nations Security Council

United Nations Security Council مجلس أمن الأمم المتحدة (Arabic) las Naciones Unidas (Spanish) |

|

|---|---|

UN Security Council Chamber in New York, also known as the Norwegian Room |

|

| Org type | Principal Organ |

| Head | Turkey (for September 2010) |

| Status | Active |

| Established | 1946 |

| Website | www.un.org/sc |

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the principal organs of the United Nations and is charged with the maintenance of international peace and security. Its powers, outlined in the United Nations Charter, include the establishment of peacekeeping operations, the establishment of international sanctions, and the authorization of military action. Its powers are exercised through United Nations Security Council Resolutions.

The Security Council held its first session on 17 January 1946 at Church House, London. Since its first meeting, the Council, which exists in continuous session, has traveled widely, holding meetings in many cities, such as Paris and Addis Ababa, as well as at its current permanent home in the United Nations building in New York City.

There are 15 members of the Security Council, consisting of 5 veto-wielding permanent members (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, and United States) and 10 elected non-permanent members with two-year terms. This basic structure is set out in Chapter V of the UN Charter. Security Council members must always be present at UN headquarters in New York so that the Security Council can meet at any time. This requirement of the United Nations Charter was adopted to address a weakness of the League of Nations since that organization was often unable to respond quickly to a crisis.

Contents |

Members

Permanent members

The Security Council's five permanent members have the power to veto any substantive resolution:

The five permanent members (also known as the P5 or Big 5) were drawn from the victorious powers of World War II, and at the UN's founding in 1946, the Security Council consisted of France, the Republic of China, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the USSR. There have been two seat changes since then, although not reflected in Article 23 of the Charter of the United Nations as it has not been accordingly amended:

- China's seat was originally filled by the Republic of China, but due to the stalemate of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, there have been two states claiming to represent China since then, and both officially claim each other's territory. In 1971, the People's Republic of China was awarded China's seat in the United Nations by UN General Assembly Resolution 2758, and the Republic of China (based in Taiwan) soon lost membership in all UN organizations.

- Russia, being the legal successor state to the Soviet Union after the latter's collapse in 1991, acquired the originally-Soviet seat, including the Soviet Union's former representation in the Security Council.

The five permanent members of the Security Council are the only countries recognized as nuclear-weapon states (NWS) under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, as they are the five countries that tested nuclear weapons before 1967.

The Permanent Representatives of the U.N. Security Council permanent members are Li Baodong (China), Gérard Araud (France), Vitaly Churkin (Russia), Mark Lyall Grant (United Kingdom), and Susan Rice (United States).[3]

Non-permanent members

Ten other members are elected by the General Assembly for two-year terms starting on 1 January, with five replaced each year. The members are chosen by regional groups and confirmed by the United Nations General Assembly. The African bloc chooses three members; the Latin America and the Caribbean, Asian, and Western European and Others blocs choose two members each; and the Eastern European bloc chooses one member. Also, one of these members is an "Arab country," alternately from the Asian or African bloc.

The current elected members, with the regions they were elected to represent and their Permanent Representatives, are:

|

|

President

The role of president of the Security Council involves setting the agenda, presiding at its meetings and overseeing any crisis. The President is authorized to issue both presidential statements (subject to consensus among Council members) and notes,[4][5] which are used to make declarations of intent that the full Security Council can then pursue.[5] The Presidency rotates monthly in alphabetical order of the Security Council member nations' names in English and is held by Turkey for the month of September 2010.

Veto power

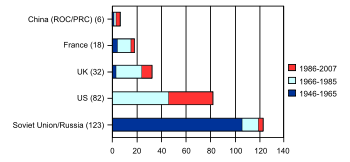

Under Article 27 of the UN Charter, Security Council decisions on all substantive matters require the affirmative votes of nine members. A negative vote, or veto, also known as the rule of "great Power unanimity", by a permanent member prevents adoption of a proposal, even if it has received the required number of affirmative votes (9). Abstention is not regarded as a veto despite the wording of the Charter. Since the Security Council's inception, China (ROC/PRC) has used its veto 6 times; France 18 times; Russia/USSR 123 times; the United Kingdom 32 times; and the United States 82 times. The majority of Russian/Soviet vetoes were in the first ten years of the Council's existence. Since 1984, China and France have vetoed three resolutions each; Russia/USSR four; the United Kingdom ten; and the United States 43.

Procedural matters are not subject to a veto, so the veto cannot be used to avoid discussion of an issue.

Status of non-members

A state that is a member of the UN, but not of the Security Council, may participate in Security Council discussions in matters by which the Council agrees that the country's interests are particularly affected. In recent years, the Council has interpreted this loosely, allowing many countries to take part in its discussions. Non-members are routinely invited to take part when they are parties to disputes being considered by the Council.

Role

Under Chapter Six of the Charter, "Pacific Settlement of Disputes", the Security Council "may investigate any dispute, or any situation which might lead to international friction or give rise to a dispute". The Council may "recommend appropriate procedures or methods of adjustment" if it determines that the situation might endanger international peace and security. These recommendations are not binding on UN members.

Under Chapter Seven, the Council has broader power to decide what measures are to be taken in situations involving "threats to the peace, breaches of the peace, or acts of aggression". In such situations, the Council is not limited to recommendations but may take action, including the use of armed force "to maintain or restore international peace and security". This was the basis for UN armed action in Korea in 1950 during the Korean War and the use of coalition forces in Iraq and Kuwait in 1991. Decisions taken under Chapter Seven, such as economic sanctions, are binding on UN members.

The UN's role in international collective security is defined by the UN Charter, which gives the Security Council the power to:

- Investigate any situation threatening international peace;

- Recommend procedures for peaceful resolution of a dispute;

- Call upon other member nations to completely or partially interrupt economic relations as well as sea, air, postal, and radio communications, or to sever diplomatic relations;

- Enforce its decisions militarily, or by any means necessary;

- Avoid conflict and maintain focus on cooperation.

They also recommend the new Secretary-General to the General Assembly.[7]

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court recognizes that the Security Council has authority to refer cases to the Court, where the Court could not otherwise exercise jurisdiction.[8] The Council exercised this power for the first time in March 2005, when it referred to the Court “the situation prevailing in Darfur since 1 July 2002”;[9] since Sudan is not a party to the Rome Statute, the Court could not otherwise have exercised jurisdiction.

Responsibility to protect

Security Council Resolution 1674, adopted on 28 April 2006, "reaffirms the provisions of paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document regarding the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity".[10] The resolution commits the Council to action to protect civilians in armed conflict.

Resolutions

The UN Charter is a multilateral treaty. It is the constitutional document that distributes powers and functions among the various UN organs. It authorizes the Security Council to take action on behalf of the members, and to make decisions and recommendations. The Charter mentions neither binding nor non-binding resolutions. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) advisory opinion in the 1949 "Reparations" case indicated that the United Nations Organization had both explicit and implied powers. The Court cited Articles 104 and 2(5) of the Charter, and noted that the members had granted the Organization the necessary legal authority to exercise its functions and fulfill its purposes as specified or implied in the Charter, and that they had agreed to give the United Nations every assistance in any action taken in accordance with the Charter.[11]

Article 25 of the Charter says that "The Members of the United Nations agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council in accordance with the present Charter". The Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs, is a UN legal publication that is published, says that during the United Nations Conference on International Organization which met in San Francisco in 1945, attempts to limit obligations of Members under Article 25 of the Charter to those decisions taken by the Council in the exercise of its specific powers under Chapters VI, VII and VIII of the Charter failed. It was stated at the time that those obligations also flowed from the authority conferred on the Council under Article 24(1) to act on the behalf of the members while exercising its responsibility for the maintenance of international peace and security.[12] Article 24, interpreted in this sense, becomes a source of authority which can be drawn upon to meet situations which are not covered by the more detailed provisions in the succeeding articles.[13] The Repertory on Article 24 says: "The question whether Article 24 confers general powers on the Security Council ceased to be a subject of discussion following the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice rendered on 21 June 1971 in connection with the question of Namibia (ICJ Reports, 1971, page 16)".[14]

In exercising its powers the Security Council seldom bothers to cite the particular article or articles of the UN Charter that its decisions are based upon. In cases where none are mentioned, a constitutional interpretation is required.[15] This sometimes presents ambiguities as to what amounts to a decision as opposed to a recommendation, and also the relevance and interpretation of the phrase "in accordance with the present Charter".[16]

In the preliminary rulings of the "Lockerbie" cases[17] the ICJ held that the provisions of the Montreal Convention could be preempted by Security Council resolutions pursuant to Article 25 and Article 103 of the UN Charter. Article 103 provides that in the event of conflicts with other treaty obligations, the members obligations under the Charter prevail. There is consensus that the treaty-based powers of the Security Council are limited to preemption of other treaties. The UN cannot circumvent peremptory norms and its resolutions are subject to judicial review.[18]

| UN Security Council Resolutions |

|---|

| Sources: UN Security Council · UNBISnet · Wikisource |

| 1 to 100 (1946–1953) |

| 101 to 200 (1953–1965) |

| 201 to 300 (1965–1971) |

| 301 to 400 (1971–1976) |

| 401 to 500 (1976–1982) |

| 501 to 600 (1982–1987) |

| 601 to 700 (1987–1991) |

| 701 to 800 (1991–1993) |

| 801 to 900 (1993–1994) |

| 901 to 1000 (1994–1995) |

| 1001 to 1100 (1995–1997) |

| 1101 to 1200 (1997–1998) |

| 1201 to 1300 (1998–2000) |

| 1301 to 1400 (2000–2002) |

| 1401 to 1500 (2002–2003) |

| 1501 to 1600 (2003–2005) |

| 1601 to 1700 (2005–2006) |

| 1701 to 1800 (2006–2008) |

| 1801 to 1900 (2008–2009) |

| 1901 to 2000 (2009–present) |

Security Council Resolutions are legally binding if they are made under Chapter VII (Action with Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression) of the Charter.

There is a general agreement among legal scholars outside the organization that resolutions made under Chapter VI (Pacific Settlement of Disputes) are not legally binding.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] One argument is that since they have no enforcement mechanism, except self-help, they may not be legally binding.[28] Some States give constitutional or special legal status to the UN Charter and Security Council resolutions. In such cases non-recognition regimes or other sanctions can be implemented under the provisions of the laws of the individual member states.[29]

The Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs was established because "Records of the cumulating practice of international organizations may be regarded as evidence of customary international law with reference to States' relations to the organizations."[30] The repertory cites the remarks made by the representative of Israel, Mr Eban, regarding a Chapter VI resolution. He maintained that the Security Council's resolution of 1 September 1951 possessed, within the meaning of Article 25, a compelling force beyond that pertaining to any resolution of any other organ of the United Nations, in his view the importance of the resolution had to be envisaged in the light of Article 25, under which the decisions of the Council on matters affecting international peace and security assumed an obligatory character for all Member States. The Egyptian representative disagreed.[31]

Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali related that during a press conference his remarks about a "non-binding" resolution started a dispute. His assistant released a hasty clarification which only made the situation worse. It said that the Secretary had only meant to say that Chapter VI contains no means of insuring compliance and that resolutions adopted under its terms are not enforceable. When the Secretary finally submitted the question to the UN Legal Advisor, the response was a long memo the bottom line of which read, in capital letters: "NO SECURITY COUNCIL RESOLUTION CAN BE DESCRIBED AS UNENFORCEABLE." The Secretary said "I got the message."[32]

Prof. Jared Schott explains that "Though certainly possessing judicial language, without the legally binding force of Chapter VII, such declarations were at worst political and at best advisory".[33]

In 1971, a majority of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) members in the Namibia advisory opinion held that the resolution contained legal declarations that were made while the Council was acting on behalf of the members in accordance with Article 24. The Court also said that an interpretation of the charter that limits the domain of binding decision only to those taken under Chapter VII would render Article 25 "superfluous, since this [binding] effect is secured by Articles 48 and 49 of the Charter", and that the "language of a resolution of the Security Council should be carefully analyzed before a conclusion can be made as to its binding effect".[34] The ICJ judgment has been criticized by Erika De Wet and others.[35] De Wet argues that Chapter VI resolutions cannot be binding. Her reasoning, in part states:

Allowing the Security Council to adopt binding measures under Chapter VI would undermine the structural division of competencies foreseen by Chapters VI and VII, respectively. The whole aim of separating these chapters is to distinguish between voluntary and binding measures. Whereas the pacific settlement of disputes provided by the former is underpinned by the consent of the parties, binding measures in terms of Chapter VII are characterised by the absence of such consent. A further indication of the non-binding nature of measures taken in terms of Chapter VI is the obligation on members of the Security Council who are parties to a dispute, to refrain from voting when resolutions under Chapter VI are adopted. No similar obligation exists with respect to binding resolutions adopted under Chapter VII... If one applies this reasoning to the Namibia opinion, the decisive point is that none of the Articles under Chapter VI facilitate the adoption of the type of binding measures that were adopted by the Security Council in Resolution 276(1970)... Resolution 260(1970) was indeed adopted in terms of Chapter VII, even though the ICJ went to some length to give the opposite impression.[36]

Others disagree with this interpretation. Professor Stephen Zunes asserts that "[t]his does not mean that resolutions under Chapter VI are merely advisory, however. These are still directives by the Security Council and differ only in that they do not have the same stringent enforcement options, such as the use of military force".[37] Former President of the International Court of Justice Rosalyn Higgins argues that the location of Article 25, outside of Chapter VI and VII and with no reference to either, suggests its application is not limited to Chapter VII decisions.[38] She asserts that the Travaux préparatoires to the UN Charter "provide some evidence that Article 25 was not intended to be limited to Chapter VII, or inapplicable to Chapter VI."[39] She argues that early state practice into what resolutions UN members considered binding has been somewhat ambiguous, but seems to "rely not upon whether they are to be regarded as "Chapter VI or "Chapter VII" resolutions [...] but upon whether the parties intended them to be "decisions" or "recommendations" ... One is left with the view that in certain limited, and perhaps rare, cases a binding decision may be taken under Chapter VI".[40] She supports the view of the ICJ that "clearly regarded Chapters VI, VII, VIII and XII as lex specialis while Article 24 contained the lex generalis ... [and] that resolutions validly adopted under Article 24 were binding on the membership as a whole".[41]

Those resolutions made dealing with the internal governance of the organization (such as the admission of new Member States) are legally binding where the Charter gives the Security Council power to make them.

If the council cannot reach consensus or a passing vote on a resolution, they may choose to produce a non-binding presidential statement instead of a Resolution. These are adopted by consensus. They are meant to apply political pressure — a warning that the council is paying attention and further action may follow.

Press statements typically accompany both resolutions and presidential statements, carrying the text of the document adopted by the body and also some explanatory text. They may also be released independently, after a significant meeting.

Criticism

There has been criticism that the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, who are all nuclear powers, have created an exclusive nuclear club that only addresses the strategic interests and political motives of the permanent members; for example, protecting the oil-rich Kuwaitis in 1991 but poorly protecting resource-poor Rwandans in 1994.[42] Critics have suggested that the number of permanent members should be expanded to include non-nuclear powers,[43] or abolishing the concept of permanency altogether.[44]

Another criticism of the Security Council involves the veto power of the five permanent nations; a veto from any of the permanent members may cripple any possible UN armed or diplomatic response to a crisis. John J. Mearsheimer claimed that "since 1982, the US has vetoed 32 Security Council resolutions critical of Israel, more than the total number of vetoes cast by all the other Security Council members."[45] The practice of the permanent members meeting privately and then presenting their resolutions to the full council as a fait accompli has also drawn fire.[46] On the other hand, a 2005 report by the American Institute for Peace on UN reform states that contrary to the equality of rights for all nations enshrined in the UN Charter, Israel continues to be denied rights enjoyed by all other member-states, and a level of systematic hostility against it is routinely expressed, organized, and funded within the United Nations system.[47] Since 1961, Israel has been barred from the Asia regional group and therefore could not even theoretically be a member of the Security Council. In 2000, it was offered limited membership in the Western European and Others Group (WEOG).

Other critics and even proponents of the Security Council question its effectiveness and relevance because in most high-profile cases, there are essentially no consequences for violating a Security Council resolution. During the Darfur crisis, Janjaweed militias, allowed by elements of the Sudanese government, committed violence against an indigenous population, killing thousands of civilians. In the Srebrenica massacre, Serbian troops committed genocide against Bosnian Muslims, although Srebrenica had been declared a UN "safe area" and was even protected by 400 armed Dutch peacekeepers.

Other critics call the UN undemocratic, representing the interests of the governments of the nations who form it and not necessarily the individuals within those nations. The UN Charter gives all three powers of the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches to the Security Council.[48]

Another concern is that the five permanent members of the UN Security Council are five of the top ten largest arms dealing countries in the world.[49]

The amount of time devoted to the Israeli-Arab conflict in the UNSC has been described as excessive by a numerous political organizations and academics, including United Nations Watch[50], the Anti-Defamation League[51], Alan Dershowitz[52], Martin Kramer, and Mitchell Bard.

Membership reform

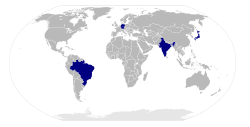

There has been discussion of increasing the number of permanent members. The countries who have made the strongest demands for permanent seats are Brazil, Germany, India, and Japan. Japan and Germany are the UN's second and third largest funders respectively, while Brazil and India are two of the largest contributors of troops to UN-mandated peace-keeping missions. This proposal has found opposition in a group of countries called Uniting for Consensus.

Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan asked a team of advisors to come up with recommendations for reforming the United Nations by the end of 2004. One proposed measure is to increase the number of permanent members by five, which, in most proposals, would include Brazil, Germany, India, Japan (known as the G4 nations), one seat from Africa (most likely between Egypt, Nigeria or South Africa) and/or one seat from the Arab League.[53] On 21 September 2004, the G4 nations issued a joint statement mutually backing each other's claim to permanent status, together with two African countries. Currently the proposal has to be accepted by two-thirds of the General Assembly (128 votes).

Chamber

The designated Security Council Chamber in the United Nations Conference Building, designed by the Norwegian architect Arnstein Arneberg, was the specific gift of Norway. The mural painted by the Norwegian artist Per Krohg depicts a phoenix rising from its ashes, symbolic of the world reborn after World War II. In the blue and gold silk tapestry on the walls and in the draperies of the windows overlooking the East River appear the anchor of faith, the wheat stems of hope, and the heart of charity.[54]

See also

- Reform of the United Nations

- Military Staff Committee, a sub-organ of the Security Council

- United Nations Security Council Counter-Terrorism Committee, a standing committee of the Security Council

- United Nations Department of Political Affairs, provides secretarial support to the Security Council

References

- ↑ (

Republic of China: 1945–1971;

Republic of China: 1945–1971;  People's Republic of China: 1971–present).

People's Republic of China: 1971–present). - ↑ (

Soviet Union: 1945–1991;

Soviet Union: 1945–1991;  Russian Federation: 1991–present).

Russian Federation: 1991–present). - ↑ List of heads of missionsPDF (60.1 KB)

- ↑ Notes by the president of the Security Council. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 UN Security Council: Presidential Statements 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ Global Policy Forum (2008): "Changing Patterns in the Use of the Veto in the Security Council". Retrieved on 25 August 2008.

- ↑ Charter of the United Nations: Chapter V: The Security Council. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ Article 13 of the Rome Statute. Retrieved on 14 March 2007.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council (31 March 2006). "Security Council Refers Situation in Darfur, Sudan, To Prosecutor of International Criminal Court". Press release. http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2005/sc8351.doc.htm. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ Resolution 1674 (2006).

- ↑ See ICJ Advisory Opinion, Reparation for Injuries Suffered in the Service of the United Nations ICJ-CIJ.org

- ↑ See page 5, The Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs, Extracts Relating to Article 25 UN.org.

- ↑ see The Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs, Extracts Relating to Article 24, UN.org.

- ↑ See Note 2 on page 1 of Sup. 6, vol. 3, Article 24.

- ↑ See Repertoire Of The Practice Of The Security Council, introductory note regarding the contents and arrangement of Chapter VIII [1].

- ↑ Schweigman, David "The authority of the Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter". 2001. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: The Hague.

- ↑ Libya v. UK and Libya v. USA.

- ↑ See for example:

- Hans-Paul Gasser,‘Collective Economic Sanctions and International Humanitarian Law – An Enforcement Measure under the United Nations Charter and the Right of Civilians to Immunity: An Unavoidable Clash of Policy Goals’, (1996) 56 ZaöRV 880–881;

- T.D. Gill, ‘Legal and Some Political Limitations on the Power of the UN Security Council to Exercise Its Enforcement Powers under Chapter VII of the Charter’(1995) 26 NYIL 33, 79;

- Alexander Orakhelashvili, 'The Impact of Peremptory Norms on the Interpretation and Application of United Nations Security Council Resolutions', The European Journal of International Law Vol. 16 no.1.

- ↑ "This clause does not apply to decisions under Chapter VII (including the use of armed force), which are binding on all member states (unlike those adopted under Chapter VI which are of a non-binding nature)." Köchler, Hans. The Concept of Humanitarian Intervention in the Context of Modern Power, International Progress Organization, 2001, ISBN 3900704201, p. 21.

- ↑ "The impact of these flaws inherent to Resolution 731 (1992) was softened by the fact that it was a non-binding resolution in terms of Chapter VI of the Charter. Consquently Libya was not bound to give effect to it. However, the situation was different with respect to Resolution 748 of 31 March 1992, as it was adopted under Chapter VII of the Charter." De Wet, Erika, "The Security Council as a Law Maker: The Adopion of (Quasi)-Judicial Decisions", in Wolfrum, Rüdiger and Röben, Volker. Developments of International Law in Treaty Making, Springer, 2005, ISBN 3540252991, p. 203.

- ↑ "There are two limitations on the Security Council when it is acting under Chapter VI. Firstly, recommendations of the Council under Chapter VI are not binding on states." Werksman, Jacob. Greening International Institutions, Earthscan, 1996, ISBN 1853832448, p. 14.

- ↑ "Chapter VI exhorts members to settle such claims peacefully and submit them for mediation and arbitration to the United Nations. Chapter VI, however, is not binding – in other owrds, there is no power to compel states to submit their disputes for arbitration or mediation by the United Nations." Matthews, Ken. The Gulf Conflict and International Relations, Routledge, 1993, ISBN 041507519X, p. 130.

- ↑ Within the framework of Chapter VI the SC has at its disposal an 'escalation ladder' composed of several 'rungs' of wielding influence on the conflicting parties in order to move them toward a pacific solution... however, the pressure exerted by the Council in the context of this Chapter is restricted to non-binding recommendations." Neuhold, Hanspeter. "The United Nations System for the Peaceful Settlement of International Disputes", in Cede, Franz & Sucharipa-Behrmann, Lilly. The United Nations, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Jan 1, 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ "The responsibility of the Council with regard to international peace and security is specified in Chapters VI and VII. Chapter VI, entitled 'Pacific Settlements of Disputes', provides for action by the Council in case of international disputes or situations which do not (yet) post a threat to international peace and security. Herein its powers generally confined to making recommendations, the Council can generally not issue binding decisions under Chapter VI." Schweigman, David. The Authority of the Security Council Under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Jan 1, 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ "Under Chapter VI the Security Council can only make non-binding recommendations. However, if the Security Council determines that the continuance of the dispute constitutes a threat to the peace, or that the situation involves a breach of the peace or act of aggression it can take action under Chapter VII of the Charter. Chapter VII gives the Security Council the power to make decisions which are binding on member states, once it has determined the existence of a threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression." Hillier, Timothy, Taylor & Francis Group. Sourcebook on Public International Law, Cavendish Publishing, ISBN 1843143801, 1998, p. 568.

- ↑ "Additionally it may be noted that the Security Council cannot adopt binding decisions under Chapter VI of the Charter." De Hoogh, Andre. Obligations Erga Omnes and International Crimes, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, p. 371.

- ↑ "One final point must be noted in connection with Chapter VI, and that is that the powers of the Security Council are to make "recommendations." These are not binding on the states to whom they are addressed, for Article 25 relates only to "decisions." Philippe Sands, Pierre Klein, D. W. Bowett. Bowett's Law of International Institutions, Sweet & Maxwell, 2001, ISBN 042153690X, p. 46.

- ↑ Magliveras, Konstantinos D. Exclusion from Participation in International Organisations, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1 Jan 1999, p. 113.

- ↑ See National implementation of United Nations sanctions: a comparative study, by Vera Gowlland-Debbas, Djacoba Liva Tehindrazanarivelo, Brill, 2004, ISBN 9004140905; and Recognition and the United Nations, by John Dugard, Cambridge University Press, 1987, ISBN 0949009008.

- ↑ See "Ways and means for making the evidence of customary international law more readily available", Report of the International Law Commission, 1950 [2]

- ↑ Repertory of Practice of United Nations Organs, Article 25, Sup. 1, Vol 1, para 5–9. [3].

- ↑ Unvanquished: a U.S.-U.N. saga, By Boutros Boutros-Ghali, I.B. TAURIS, 1999, ISBN 186064497X, p. 189.

- ↑ Chapter VII as Exception: Security Council Action and the Regulative Ideal of Emergency, page 56

- ↑ Legal Consequences for States of the Continued Presence of South Africa in Namibia (South West Africa) notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970), Advisory Opinion of 21 June 1971 at paragraphs 87–116, especially 113: "It has been contended that Article 25 of the Charter applies only to enforcement measures adopted under Chapter VII of the Charter. It is not possible to find in the Charter any support for this view. Article 25 is not confined to decisions in regard to enforcement action but applies to "the decisions of the Security Council" adopted in accordance with the Charter. Moreover, that Article is placed, not in Chapter VII, but immediately after Article 24 in that part of the Charter which deals with the functions and powers of the Security Council. If Article 25 had reference solely to decisions of the Security Council concerning enforcement action under Articles 41 and 42 of the Charter, that is to say, if it were only such decisions which had binding effect, then Article 25 would be superfluous, since this effect is secured by Articles 48 and 49 of the Charter."

- ↑ "The International Court of Justice took the position in the Namibia Advisory Opinion that Art. 25 of the Charter, according to which decisions of the Security Council have to be carried out, does not only apply in relation to chapter VII. Rather, the court is of the opinion that the language of a resolution should be carefully analyzed before a conclusion can be drawn as to its binding effect. The Court even seems to assume that Art. 25 may have given special powers to the Security Council. The Court speaks of "the powers under Art. 25". It is very doubtful, however, whether this position can be upheld. As Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice has pointed out in his dissenting opinion: "If, under the relevant chapter or article of the Charter, the decision is not binding, Article [69/70] 25 cannot make it so. If the effect of that Article were automatically to make all decisions of the Security Council binding, then the words 'in accordance with the present Charter' would be quite superfluous". In practice the Security Council does not act on the understanding that its decisions outside chapter VII are binding on the States concerned. Indeed, as the wording of chapter VI clearly shows, non-binding recommendations are the general rule here." Frowein, Jochen Abr. Völkerrecht – Menschenrechte – Verfassungsfragen Deutschlands und Europas, Springer, 2004, ISBN 3-540-23023-8, p. 58.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 De Wet, Erika. The Chapter VII Powers of the United Nations Security Council, Hart Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1-84113-422-8, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Zunes, Stephen, "International law, the UN and Middle Eastern conflicts". Peace Review, Volume 16, Issue 3 September 2004 , pages 285 – 292:291.

- ↑ Higgins, Rosalyn. "The Advisory opinion on Namibia*: Which un Resolutions are Binding under Article 25 of the Charter?" International & Comparative Law Quarterly (1972), 21 : 270–286:278.

- ↑ Higgins, Rosalyn. "The Advisory opinion on Namibia*: Which un Resolutions are Binding under Article 25 of the Charter?" International & Comparative Law Quarterly (1972), 21 : 270–286:279.

- ↑ Higgins, Rosalyn. "The Advisory opinion on Namibia*: Which un Resolutions are Binding under Article 25 of the Charter?" International & Comparative Law Quarterly (1972), 21 : 270–286:281–2.

- ↑ Higgins, Rosalyn. "The Advisory opinion on Namibia*: Which un Resolutions are Binding under Article 25 of the Charter?" International & Comparative Law Quarterly (1972), 21 : 270–286:286.

- ↑ Rajan, Chella (2006). "Global Politics and InstitutionsPDF (449 KB)". Frontiers of a Great Transition. Vol. 3. Tellus Institute.

- ↑ "India makes strong case for UNSC expansion". HindustanTimes.com. 13 November 2005. Archived from the original on 8 September 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20060709065814/http://www.hindustantimes.com/news/6640_1544815,001600320005.htm.

- ↑ "Statement by Canadian Ambassador Allan Rock on Security Council Reform". Global Policy Forum. 12 July 2005. http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/reform/statements/2005/0712canada.htm. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ↑ John J. Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt. "The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy". KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series. Harvard University. http://ksgnotes1.harvard.edu/Research/wpaper.nsf/rwp/RWP06-011. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ↑ Empowering the Peoples in their United Nations – UN Reform – Global Policy Forum. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ American interest and UN reform. REPORT OF THE TASK FORCE ON THE UNITED NATIONS, United States Institute of Peace, 2005, USIP.org

- ↑ Creery, Janet (1994). Read the fine print first: Some questions raised at the Science for Peace conference on UN reform. Peace Magazine. Jan–Feb 1994. p. 20. Retrieved on 7 December 2007.

- ↑ Global Issues – The arms trade is big business by Anup Shah. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ↑ http://www.unwatch.org/site/c.bdKKISNqEmG/b.1359197/k.6748/UN_Israel__AntiSemitism.htm UN, Israel & Anti-Semitism

- ↑ http://www.adl.org/international/Israel-UN-1-introduction.asp Israel at the UN: Progress Amid A History of Bias

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/alan-dershowitz/the-united-nations-kangar_b_223424.html The United Nations Kangaroo "Investigation" of Israeli "War Crimes"

- ↑ "UN Security Council Reform May Shadow Annan's Legacy". Voice Of America. 1 November 2006. http://www.voanews.com/english/2006-11-01-voa46.cfm. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ↑ UN website.

External links

- UN Security Council — official site

- UN Democracy: hyperlinked transcripts of the United Nations General Assembly and the Security Council

- Global Policy Forum – UN Security Council

- Security Council Report — timely, accurate and objective information and analysis on the Council's activities

- Center for UN Reform Education – objective information on current reform issues at the United Nations

- Hans Köchler, The Voting Procedure in the United Nations Security CouncilPDF (238 KB)

- Reform the United Nations website — tracking developments

- History of the United Nations — UK Government site

- Who will be the next Secretary General?

- (French) The different projects of reform (G4, Africa Union, United for consensus) (2006)

- UNSC cyberschool

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||